September 30, 2011

Wendy Thompson

Editor-in-Chief

Limelight, Top 10 Most Interesting People 2011

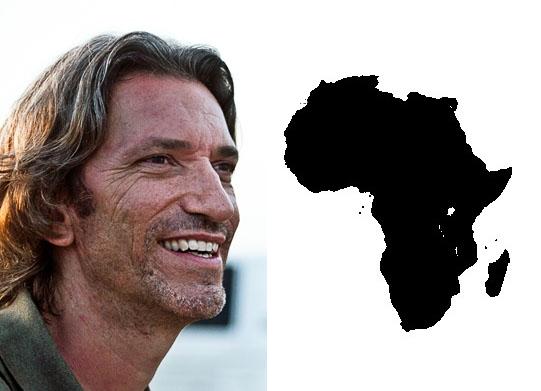

As John Prendergast cautiously approaches a podium to speak at his many engagements, his uncertainty does not reflect his lack of confidence. Instead, Prendergast must time his approach to the podium to coincide with the end of the speaker’s roster. The roster is a list of his many accomplishments. The extensive list begins with his Enough Project, which he co-founded to end genocide and crimes against humanity.

Name-dropping is highly applauded in Prendergast’s case, because each name signifies a crucial person who has joined in the fight for human rights. Each name reflects the extent to which he has lobbied to help the neediest and most vulnerable people in the world obtain the rights to live healthy, full lives. In that laudable fight for human rights — particularly in Africa — Prendergast has worked with stalwarts such as former President Bill Clinton, actors George Clooney, Don Cheadle, Brad Pitt and Matt Damon, NBA star Tracy McGrady and other NBA players and is currently working with actor Ryan Gosling.

As a young boy, Prendergast would never haveimagined the extent of his influence as a man in a world filled with atrocities. He recalls lamenting his teenage years as a dreadful period in his formative life. It wasn’t the abusive father and the extreme case of acne that distressed him most. It was the feeling that no one cared enough or thought him worthy enough to be loved. Those feelings were mirrored in the people and children he would later encounter at a local homeless shelter.

“I felt very unloved and very unlovable…I didn’t feel worthy…I just had that self-denigration that kids from abusive households often have, the feeling of lack of self-worth,” he remembers.“So here I am hanging around with these kids in that shelter that day and their faces and their approach…was one of total acceptance, was one of total connection in a way that made me feel really good about myself.”

“I think that having a difficult and at times abusive relationship between father and son can have any number of different impacts,” he says candidly. “I wish there was sort of a formula where everybody knows that if a father does this then …this is how the son will turn out. Then you can fix that, because you know it…There’s a thousand different ways you can react, and I was a really sensitive really sort of combative kid. So my reaction was one of very strong rejection of what I felt to be a very unfair situation between [him]and me.”

Prendergast says he marshaled those emotions over the years and channeled them toward causes like Darfur and people who were also victims of circumstance. “That unfairness, that [feeling]of unfairness, morphed,” he says. “It translated into a worldview, an outlook that raged against unfairness in the world wherever I saw it…It was a very early ingrained feeling, [an]embedded feeling that took form slowly but surely first in my work with kids who were down and out here in the U.S…then more broadly over time in Africa where I saw the biggest set of unfair circumstances.”

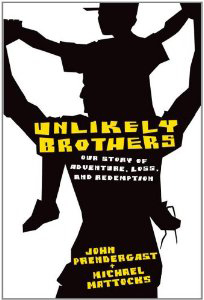

At an early age, Prendergast understood what he lacked and used that lack within himself to find others who often needed a hand up. In writing his latest book “Unlikely Brothers” (co-authored by Michael Mattocks), he recalls memories of his early life as a 20-year-old young man befriending a 7-year-old boy at a homeless shelter in Washington, D.C. That young boy, Michael Mattocks, who was living with his mother and brothers in the shelter, would become an integral part of Prendergast’s education about human rights in the U.S. Over time, despite the fact that Mattocks was poor and black and Prendergast was middle class and white, they would become “unlikely brothers” with both young men learning lifelong lessons about friendship, family, loyalty and respect. Those early days at the shelter with Mattocks provided fertile ground for the growth of the international human rights activists Prendergast would later become.

“I think there were small things at first,” he remembers. “I started going to homeless shelters and working with the folks that were living there and just spending time and trying to understand what left them in their situation and trying to work with the system to try to find some form of solution to the set of issues that had led them to the shelter in the first place,” he recalls. “I think those are basic human rights. So I go all the way to Africa to work on human rights…and I think there are so many issues here in the United States where people’s fundamental rights are being violated frequently and regularly. We have a lot of work to do here.”

He is often surprised and amazed at the masses of people in the U.S. who have taken the fight for human rights seriously and begun the journey with him in protecting the rights of others.

“It’s amazing how many thousands and thousands of people that I come across every month who are equally committed to making a difference outside our borders as they are inside our borders of the United States…I’m much more encouraged than if I [had]just stayed in Washington, D.C. in the beltway, I would probably think, America doesn’t care…especially with the political environment the way it is, especially going around the states and meeting with young people…Everywhere I’ve gone people are very excited to get involved.”

This outreach was overwhelmingly evident during the massive genocide of the people of Darfur in Africa.

“Because of the Darfur genocide in the earlier part of the last decade created a huge movement in the United States of people who were willing to get involved, go to rallies, write letters to their congress people,” he says. “Now we’ve had similar outpouring in the birth of the new nation of South Sudan.”

Today, as he travels with Mattocks around the U.S. discussing their book, Prendergast admits that he is on a new unfamiliar journey: marriage. As a 7-year-old, Mattocks once relied on Prendergast for guidance; however, the roles have reversed. Mattocks, a happily married father of five boys, is guiding and sharing life lessons with Prendergast as he embarks on his new marriage. Prendergast confides that throughout his life, he assumed that he would never be afforded the joys of marriage and family life – that he would have to be content as a man dedicated to work.

“By far the most important thing to me is that I just got married, so I have to spend time working and making that a success. So that’s my top priority.”

He says now his new relationship is the great work in progress, in addition to his fight for human rights.

Prendergast currently teaches at Yale University in Connecticut, works with his Enough Project and lives in both New York and Washington, D.C. equally. He is also working on a new book with actor Ryan Gosling.

Enough Project

1333 H St. NW, 10th Floor

Washington, DC 20005

http://www.enoughproject.org