September 1, 2013

September 1, 2013

Lauren Staehle

News Writer

Book Review

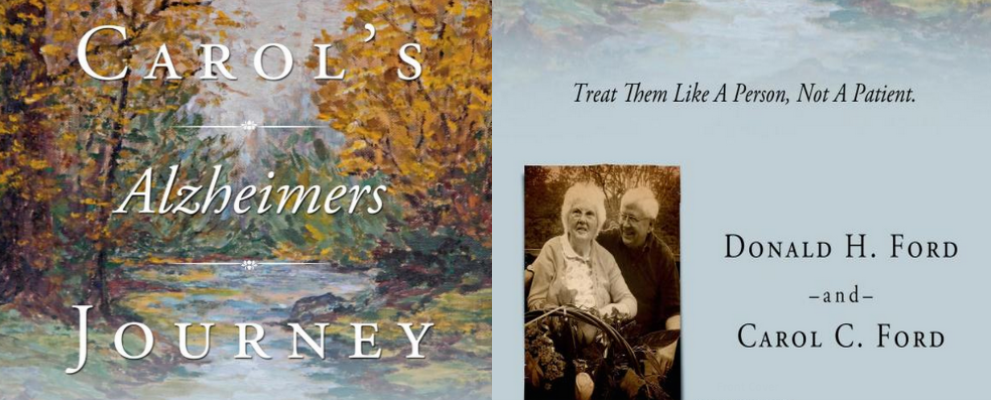

Donald Ford is a psychology professional and has written seven scholarly books over the course of his career. Once his wife, Carol, was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, he decided to share his personal experience and his developmental model of care in his latest book, Carol’s Alzheimer’s Journey. Here, he lays out methods that caregivers can use to make Alzheimer’s sufferers feel more in control of their own lives, even after communication with words becomes impossible.

Q: Is this your first book? When did you start and finish this book?

A: I’ve written seven other books, but they were all scholarly books. I started this one about four months after my wife died of Alzheimer’s, and I finished it about a year later.

Q: Why did you want to write this book; is it a personal book?

A: My life, my career were spent in various different roles, helping people solve their problems, and I helped my wife with her mother when she had Alzheimer’s, and when we learned that Carol was going to have to deal with that at the end of her life we talked about it and I made it clear that I was not going to let her go into a nursing home and I was going to use what I had learned in the past to create a home care program. She said that if it worked, we ought to share it with other people.

Q: In witnessing people close to you struggle with Alzheimer’s, what were some of the common, “traditional” methods you saw being used for treatment? Why are these ineffective?

A: First of all, I lived in a nursing home for seven weeks while my wife was there for some rehab, so I observed first hand what was happening to these people. In general, they spend most of their time with nothing to do. They are bored, and when you’re bored you either get down in the dumps, or start trying to find things to do. Second problem is, usually the staff is largely responsible for physical care, giving you your meds and getting you ready for bed, and if someone wants to have other kinds of interaction with the staff, they don’t have time. So when you’re lonely and you’re bored, you might do things like wandering through other people’s rooms. You might even try to walk out the door, go somewhere else. We interpret the behavior of people in these circumstances as abnormal or sick, when in fact, most of their behavior can be seen as things we all do, but they are different in form because of where they are living and the kind of people they are around.

Q: How is your focus on the whole person and their humanity different from typical methods of care?

A: First of all, a person with Alzheimer’s, and let’s just talk about the late stages of Alzheimer’s where often they can’t communicate with words, they can’t walk, they can’t take care of themselves. That is the state, for example, that my wife was in for the last 3 years of her 11 years with Alzheimer’s. Now, they’re still a person with all the characteristics that younger persons have, they can still think, they can still get pleasure out of doing things that they have gotten pleasure out of earlier in their life, they can speak sometimes in their own jargon, and if you’re around them a lot you can begin to get the message. The fact that these people can’t use their own words makes other people infer that they are dumb, that they have something wrong with them. The important thing is to say that they are still a person, they still have all these properties. There are some limitations they have, so you have to find other ways [to communicate]. What we did with the care program I created was to identify all the things in [Carol’s] life that she had gotten pleasure out of and the way she got that pleasure, like choral singing or being outdoors with mother nature, and then once she was in that late stage where she had all those limitations, we would invent behavior episodes where she could do something that she had enjoyed doing in the past within the limits that she had. For example, while she couldn’t go out and walk in Mother Nature anymore, she could ride around in a golf cart with us, looking at it and enjoying it.

Q: Can you explain how a person’s memory works and how Alzheimer’s affects the memory?

A: Well, let’s talk about the way memory works for all of us. Memories occur because we’re doing something in a certain context with certain things around us, like other people, and all those elements are sometimes called retrieval cues, because they activate memory processes. And memories aren’t like having a book on a shelf somewhere, we don’t store memories, memories are reconstructions from past experiences that have left “deposits” in our brain. Now when a person doesn’t remember something, that doesn’t mean that it might not be possible to help them remember it, if you can change the retrieval cues. For example, if my wife didn’t remember me when I came into the house from being outdoors, and she would ask who I was, and I would say, “Well darling, I’m here to have some fun with you.” I wouldn’t worry about her not remembering I was her husband. But, later on I would arrange for us to be in a different context, doing things we had often done together, and there were a lot more retrieval cues, and in that circumstance she would remember me. It isn’t that they can’t regenerate those things, but because of their difficulties in communicating, they live in the “here and now,” and the best way to work with them is to focus on the here and now. You don’t talk about long-term goals; you talk about what we can do today.

Q: In your model of care, you emphasis the importance of personal goals and satisfying life experiences for someone with Alzheimer’s. What effect does this have?

A: You turn things into what I call a behavior episode, for example, first thing in the morning when I’m waking her up, I would turn on music that she liked, so that she would wake up to that, so waking up wasn’t a bad thing, it had some pleasure in it. Then we would turn everything into a goal, “well let’s go to the bathroom and have a bath and get dressed,” so we would go do that. And when we would get to the point of getting dressed, we would get a couple of garments and hold them up and I’d say “which one do you want to wear today?” and she might like one more than the other and she would touch one or point to one and that gave her the feeling that she was still in some control of her life, and when she was accomplished, she felt good about it. So you take simple things in life and you turn them into a goal-directed activity and you help her succeed at it. Just the fact that you can do that and succeed at it says, “I’m still a person and I have some control in my life.” The worst thing we do to them is put them in a nursing home where they have no control over their life, where they have nothing to do except whatever the caregivers want them to do, and they can’t interact with other people.

Q: What is the importance of words or names in the thinking process and how can caregivers improve communication with an Alzheimer’s patient who is struggling to use words?

A: Let me give you an example: a woman was in a care circumstance and she could not communicate. Her aid invented a book with pictures in it, like a telephone, a bathroom pot, a glass of water, a record, this woman couldn’t talk, but she could leaf through her book and point to something and the caretaker would understand. When she would point to the telephone it meant she wanted to talk to her parents, so she would call them and talk to them for a while. So that’s an example of how even though words aren’t functional for most of their behavior, you can find other ways that they can still deal with to communicate with them.

Q: What is the importance of family and the continuation of regular family life to someone with Alzheimer’s?

A: Well of course in any period of life, what a family means to you and whether it’s good or bad varies from person to person. Some people are glad not to have their families around. But, in general, family members are people that they have a lot of experiences with, a lot of those experiences have been happy or pleasurable, and so family members who are willing to spend time and energy in helping make their current life satisfying can be very effective. And when [family members]don’t come to see them, if they are in a nursing home for example, they might remember their names, but they know they are lonely, and that somebody hasn’t come to see them.

Q: Why do so many caregivers develop feelings of exhaustion and burnout? How does your method prevent those feelings?

A: You and I and everybody else have the same basic processes that guide our life, we like to have goals, we like to be able to do things to accomplish those goals, when we accomplish those goals, we feel good about ourselves, and that’s the flow of life. Now you take a person and put them in a nursing home to be an aid, and they can’t fix what is wrong with the person they are trying to help, they can’t do anything to make them feel better because they only have time to take them to the bathroom, help them get dressed and take them to someplace to eat. You get to do anything to make you feel like you’ve done something worthwhile. That’s why they get burned out. When you change to a method like I used with Carol, the caregivers everyday accomplish things with the person they are caring for that they feel good about, that please them.