November 30, 2011

Miriam Laufer

News Writer

Book Review

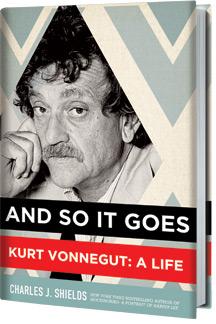

“Someone else could cobble together a so-so version of your life just by mining what’s stored in library boxes and electronic files. But I’m the guy for the job — for doing it right, that is,” wrote Charles J. Shields to Kurt Vonnegut, Jr. in 2006. Shields’ new biography, And So It Goes: Kurt Vonnegut: A Life, the first and only authorized biography on Kurt Vonnegut Jr., is thorough and explores many previously unexamined facets of Vonnegut’s life. Shields has a knack for fleshing out the most interesting and occasionally salacious details, but with an even-handed treatment of the author.

The character that emerges from Shields’ portrait is of a petulant, embittered, and attention-seeking man, who felt that his parents and brother misunderstood him, that publishers, editors, and critics undervalued him, and that even his first wife Jane, mother of their three children, never really loved him. Yet, Shields reveals that Vonnegut could be remarkably kind, charming, and thoughtful. While teaching in the creative writing program at the University of Iowa, he noticed that the anonymous critiquing sessions that welcomed students from all classes had become a platform for bullies. He suggested that “sections should meet separately…with an instructor to guide the discussion,” that submissions should no longer be anonymous, and overly subjective criticism banned. All of these changes were implemented. Later in his career, after experiencing fame, a young writer disguised himself as a reporter in order to meet with Vonnegut. He called the young man’s bluff and met with him anyway, encouraging him to write the article he had concocted in a fake story.

The Vonnegut estate refused Shields’ request to quote directly from the 1,500 letters that he acquired over the course of his research. According to Shields, this is because the estate handlers did not want the image of Vonnegut, as the crotchety, Mark Twain-like figure, to change. In the book, he discusses Vonnegut’s decision to adopt the Twain style and concludes that it was a very deliberate affectation. Although Vonnegut is often associated with the Left due to his anti-war ethos, Shields argues that he was in fact a reactionary and an active capitalist. Vonnegut’s numerous stocks and investments in large corporations support this claim. The content of the letters, however, is pervasive throughout the biography. Two hundred were to Vonnegut’s sometime friend, editor, and agent, Knox Burger, to whom the biography is dedicated. Vonnegut wrote to Burger about his difficulties getting published in the early years. Later, he wrote letters about those who failed to take his works seriously, being “cooped up with all these kids,” and also, about his affairs.

The first serious affair, which began a relationship that would last in some capacity for the rest of his life, was with Lora Lee Wilson, a student in one of his creative writing classes at Iowa. Despite his lifelong love of women, Shields shows that Vonnegut held some very traditional ideas about women’s roles, which affected his relationship with Jane, his wife of thirty-four years. While Vonnegut wrote, Jane ran the household and raised the children, including his nephews. Shields emphasizes that “he expected Jane to be a traditional wife who would blend her identity with his.” When they fought, his reaction was to run off and sometimes to chase after other women. After their divorce, they remained friends and he continued to write long letters to her. Occasionally, he would write a letter to Jane and then a letter immediately afterwards to a girlfriend. His second wife, Jill, whom Shields was not able to interview, appears in the book as a difficult, demanding woman who wanted to control with whom Vonnegut socialized. Their marriage was also fraught with tension and included several periods of separation.

Vonnegut was a loving, if distant, father to his three children with Jane. Additionally, he was supportive of his sister Alice’s three older boys. Alice was his crony from childhood and companion. He wrote of her in his science fiction novel Slapstick; or Lonesome No More! that “she was the person I had always written for.” With a sense of the coincidental worthy of his subject, Shields recounts the death of Alice’s husband Jim in a train accident hours before Alice succumbed to terminal breast cancer. The chapter, “The Dead Engineer,” was written for the engineer whose fatal heart attack led to the derailing of the train over Newark Bay where 46 passengers, including Jim Adams, drowned. Although Shields was unable to interview Vonnegut’s son Mark for the book, his daughters Edith and Nannette — referred to as “Edie” and “Nanny,”– and his nephews Jim Adams and Kurt Adams, known as “Tiger,” were candid about their experiences with their father and uncle. “I don’t remember my father being that one-on-one as a kid,” said Edie, who did recall one particular incident, “I remember being asleep and my father carrying me…it’s the only time I really remember being carried.” According to Tiger, “He had a cruel side…and that’s why it always struck me…the guy that you would imagine from his writing and the guy that is the real guy.”

In addition to the most private details of Vonnegut’s life, Shields also places his works in a biographical context. Shields notes that unsatisfactory sexual experiences are a pattern in Vonnegut’s earlier works, from Player Piano to Cat’s Cradle. “His affair with Loree [Lora Lee Wilson],” Shields writes, “would change the way he wrote about relationships in his novels.” She is the model for Montana Wildhack in Slaughterhouse-Five with whom Billy Pilgrim has a mutually satisfying sexual relationship. Unlike other recent biographers, Shields does an excellent job of removing himself from the text. He does this to such an extent that he refers to “a visitor,” who asked Vonnegut if he believed in God hours before his death. That visitor was Shields. Throughout the book, he places the reader in the head of Vonnegut and his friends and family, particularly Jane. Like Vonnegut, his style is direct, emotionally honest, and unapologetic. Shields’ rendering of Vonnegut’s life, while not flattering, still manages to be respectful and compelling in chronicling how Vonnegut captured the imagination of a generation, and continues to capture young minds. “If he had been a fully mature adult, it’s likely he would not have been able to frame young adults’ worldview so well,” Shields insists. From Vonnegut’s own assessments of himself, it’s likely he would have agreed.